Q&A

Have any questions about science you want answered by an expert? Send us your questions and we will get them to the right person, who will respond as quickly as they can. The sky is the limit!

“The art and science of asking questions is the source of all knowledge.”

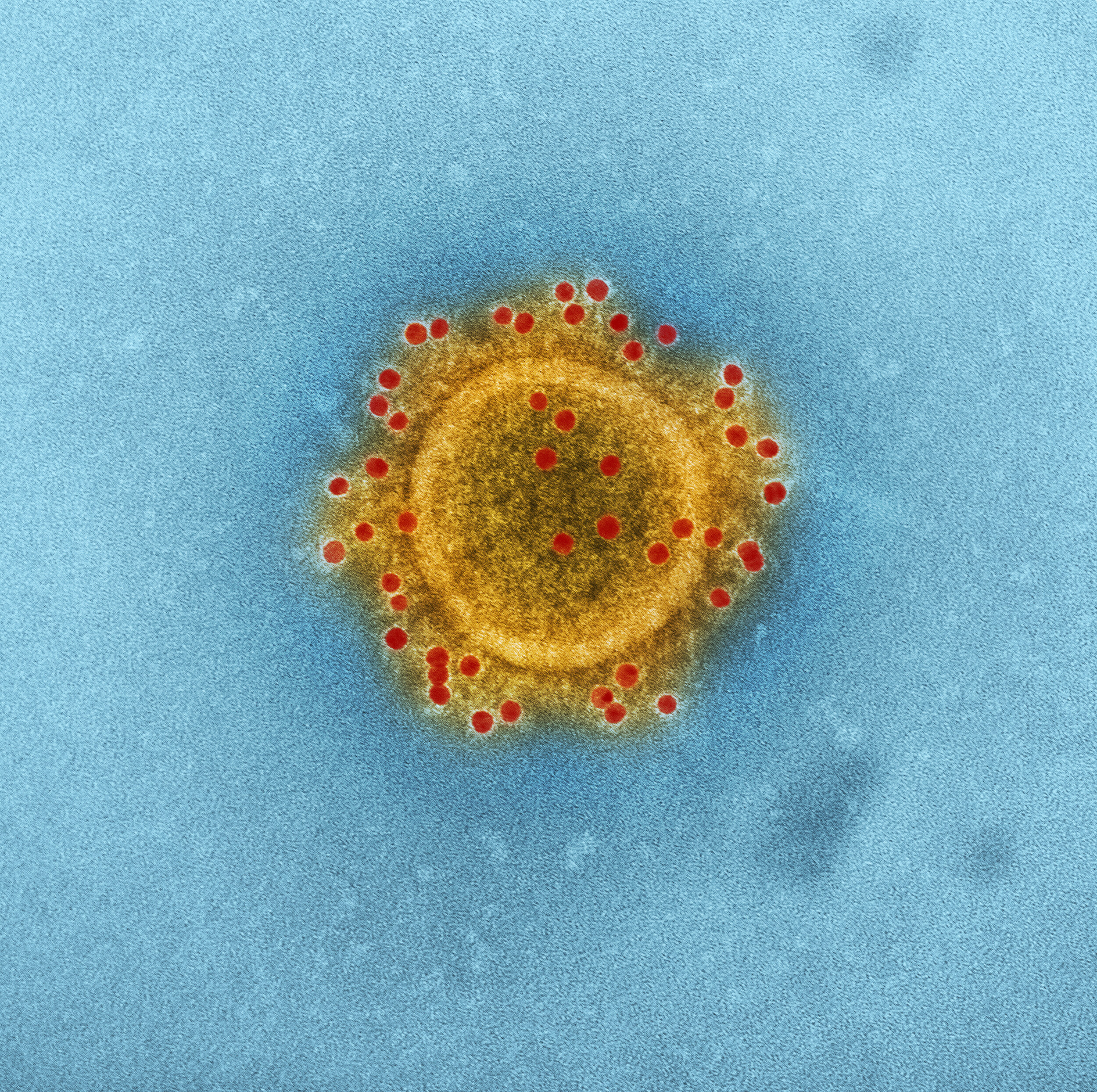

CoVID-19

I heard about a new technique called convalescent plasma transfusion that may be able to treat CoVID-19 patients. Is this a promising treatment?

There have been reports of using blood plasma from patients who have recovered from CoVID-19 as a potential treatment. This idea is not new to medicine and has been investigated for other infectious diseases such as Ebola. The logic is that those who have overcome the infection will have developed antibodies specific to the virus, and those antibodies can be collected and used to help treat someone who has yet to recover from infection.

While the theory is sound, there are a couple important things to note. First, the two studies (1,2) that investigated this treatment (termed convalescent plasma transfusion) produced results that are difficult to interpret accurately. For example, the patients that were treated did improve, but they were also being treated with several other medications, so it's difficult to know if the transfusion was responsible for the improved outcome or if it was something else. Second, although one small study of 14 people demonstrated that patients developed antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, it has not been established whether or not everyone challenged with the virus will develop a protective immune response -- this would limit the amount of plasma available for treatments.

Although the limited amount of data looks promising, it is still too early to tell if this method will emerge as a widespread treatment option for CoVID-19. We will keep you updated as more information becomes available.

-Blaide

CoVID-19

I understand that each new infection creates an opportunity for the SARS-COV-2 virus to mutate. How do you reach the conclusion that less hosts [via quarantine] can push it to evolve into a weaker form?

Every time a virus gets an opportunity to replicate is an opportunity for random mutations to occur which can give rise to new strains. How often that happens depends on the amount of errors that the virus-specific polymerase (the enzyme that replicates the genetic material) makes. We don't know enough about the genetics of the virus yet to say how quickly it will mutate.

Out of the resulting genetic diversity, viruses can arise that can better adapt to their environment. If we limit the virus’s opportunities to replicate by quarantining, then we limit the potential diversity that the virus population can have, and thus limit its ability develop beneficial mutations. Think of it like this: viruses are always wearing a tool belt and the more they replicate, the better chance they have at acquiring more tools. If we limit replication, they're stuck with only a screwdriver, and there's not a lot of opportunity for the virus to become a master carpenter. This limits the range at which it can infect and also makes it easier for us to target therapeutically, in some cases.

There’s also another way to look at this in which the virus has to make a trade-off, sacrificing its ability to cause severe disease for transmissibility, and this is now outlined at length in the article.

-Blaide

CoVID-19

I have heard that this virus doesn't like heat. In treating these patients, would it not help to apply heat, like a heating pad on their back covering the area where their lungs are?

We don't have much data on how susceptible SARS-CoV-2 is to heat stress. On principle, yes, the viability of SARS viruses can be reduced with high temperatures, but a heating pad would not do the trick. While we are not sure specifically at what temperature SARS-CoV-2 is inhibited, I would not bet on a heating pad reducing the viral load in infected lungs.

-Jason

CoVID-19

Would you explain a little more how a vaccine will help better than natural immunity? how Can immunity Be achieved through a vaccine if it cannot be achieved naturally?

This is a great question. Developing a vaccine is tricky. We need to try and find a viral protein that the immune system can recognize and develop antibodies to so the adaptive immune response can target it when exposed. If we could just choose a viral protein with a low mutation rate to target, we'd have found a vaccine for viruses like HIV a long time ago. Problem is, most proteins that are targeted by the immune response are those on the surface of the virus, and those also tend to be the most easily changed through random mutation. That's why vaccines have to go through many iterations to make sure the biology aligns with what the immune system actually tends to target within the population. Designing a vaccine is a thorough and tested process that attempts to find a robust target; if the immune system has to do this naturally via exposure, it can develop antibodies to proteins that will mutate quickly.

As for natural immunity, you can always gain natural immunity if you 1) survive the infection or 2) if the virus doesn't mutate rapidly. It's not that people aren't gaining immunity to the flu, they are. It's just they don't have immunity to the strain that comes around the next year. We are not sure yet, but it is possible that this could also apply to CoVID-19. Those that survive will probably have immunity for a time; but we are not sure how long. For this reason, it's important to develop a vaccine instead of relying on natural immunity.

-Jason and Blaide

CoVID-19

What do we expect to happen as the virus mutates?

There are currently over a million people (10^6) infected with SARS-CoV-2 and each one of those harbors at least 100,000,000 (10^8) viruses. This means that there are at least 100,000,000,000,000 (10^14) SARS-CoV-2 viruses on the planet. Every time the virus replicates, different mutants are produced. Because SARS-CoV-2 is an RNA virus the mutation rate is even higher than most DNA viruses. Together, these large numbers mean that the virus is mutating and strains of SARS-CoV-2 are being selected at nearly unfathomable rates. So, what do we expect to happen?

1) Some strains of SARS-CoV-2 will be selected to last longer in environmental reservoirs. The longer the virion can survive the more likely it is to be picked up and reproduce.

2) Some strains of SARS-CoV-2 will be selected to be more easily aerosolized. Again, there will be a selection to be more easily transmitted. For example, mutations that produce more violent coughs.

3) Other strains will no longer be detectable by current screens. After all, we are putting lots of pressure on SARS-CoV-2 to not be detected. Mutations that are not picked up by the RT- PCR tests will do better.

4) Some strains of SARS-CoV-2 will be selected to be more resistant to disinfectants.

5) Others will develop longer lag times to keep carriers asymptomatic.

6) Still other strains will move to non-human reservoirs. There are already numerous reports about SARS-CoV-2 in cats, including a tiger.

7) And still other SARS-CoV-2 strains will eventually mutate and be selected to resist drugs and antibodies that are being developed to keep the virus in check.

While all of this sounds bad, these evolutionary dynamics will almost assuredly attenuate the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Mutations that favor one trait, often come at a cost for another trait. Over the long term, we expect SARS-CoV-2 to become less virulent. Strains of SARS-CoV-2 that produce less severe disease and avoid detection should become dominant.

Does melting sea ice cause sea level to rise?

The answer is actually no. Sea ice melting doesn’t make sea level rise any more than melting ice cubes in your water glass make the glass overflow. The melting of land-based ice, though, such as the ice in glaciers, ice sheets and locked up in permafrost, does cause sea level to rise, and this is the root of the problem we are facing now.

In addition, as water melts and gets warmer, it expands, causing a further increase in sea level. This sea level rise due to ice melt and thermal expansion in the coming years will significantly impact people living in coastal cities, and should not be understated.

-Jason

Are the bees dying at an alarming rate?

A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences reported that the population of bees in the U.S. declined by 23% between 2008 and 2013.

By all reasonable standards, I would say that drastic of a decline warrants the sounding of alarms, especially given that over 3 billion dollars of our economy stems from resources dependents on bees and other pollinators. Something to keep in mind.

-Daniel

Why is the flu vaccine not 100% successful every year?

According to the CDC, the flu vaccine’s annual effectiveness is between 40-60%. The influenza vaccine, like all vaccines, introduces parts of the physical substrate of the virus to the body, effectively training your immune system to recognize the patterns present on the coat of the flu virus. The effectiveness of the vaccine depends on many factors including the strength of the persons immune system and the subtype of flu being circulated (the vaccine is most effective against Influenza B).

Think of it like playing “Where’s Waldo,” where Waldo is the flu virus. In this case, however, Waldo is wearing a different patterned shirt and workers at the CDC attempt to predict what shirt Waldo will be wearing every year so they can show it to your immune system and allow it to recognize the virus right away. However, predicting what shirt he’s (the virus) going to wear is not an easy task. Further, there are also often multiple flu viruses with multiple shirts circulating in any given year.

-Daniel

Are fossil fuels really running out?

Unfortunately, the answer is yes. Fossil fuels, such as coal, natural gas, and oil, are not inexhaustible.

Current estimates suggest we have about 50 years worth of extractable oil and natural gas left on earth, and close to 100 years of coal, assuming we continue use these fuels at our current rate. This may sound like a lot of time. However, with climate change becoming a critical global issue, we may have to leave many of these reserves untouched to avoid a major environmental collapse, which is predicted to occur when global average temperatures increase by 2°C. We are not far away. It was agreed on at the UN Paris Agreement that avoiding this threshold should be a priority for all nations.

-Jason

I heard in the news that HIV was cured in some patient from london. Could this be a cure for other patients too?

A recent case study published in Nature reports the second case ever of complete HIV remission following a stem cell transplant for treatment of Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. This report comes around 10 years after the famous “Berlin Patient,” Timothy Brown, who was the first ever case reported in the New England Journal of Medicine of complete HIV remission following similar treatment for Leukemia. Timothy Brown underwent similar stem cell therapy as the most recent patient, except he was being treated for a form of leukemia.

At this point, it is unclear why these two patients receiving similar treatments have been cured of HIV and it’s too early to tell whether or not this will yield results for all patients. However, it does provide a promising avenue of research for continuing the search for a definitive cure to one of mother nature’s deadliest viruses.

-Daniel