In California, when the fog isn’t cooling the coastal areas and the monsoon isn’t hammering the deserts, its fire season.

Every year the season lengthens. Every year the stores run out of smoke masks. Every year we look for someone to blame for the lives and homes lost. Historically, California burned, a lot. But these “megafires” we are facing now are unprecedented and as a restoration ecologist, every year I am forced to confront the toll these fires have on some of the most diverse ecosystems in the country.

Last year, I lived in Davis, California, a small town near Sacramento. Three days after I moved in, I saw smoke swirling around the hills to the West. Like any smart California ecologist, I waved my hand and decided to go camping. I awoke to a campsite filled with smoke and booked it out of the forest, listening to the radio as I drove away from what would quickly become the largest wildfire in California history (for now). Two months after the ignition, the Mendocino Complex smoldered into nothing and I spent a few days exploring the ash-ladened oak woodlands, knowing that after the winter rains, this ecosystem would rebound.

This is what intrigues me about fire. For the animals that flee from it, the trees that die from it, and for the people who seek to put them out, fires are a destructive force. Flaming embers jump from tree to tree. Meter-high flames race through the dry grass. Smoke chokes wildlife and people alike. But given our knowledge of past fires, we assume the ecosystem bounces back.

Forest fires are a natural part of ecosystems, creating new habitat for a green and thriving understory. Image credit: Yale e360

Most ecosystems in California have evolved with a moderate fire regime: frequent, low-severity fires that clear out the understory, releasing many plant species from competition and creating new habitat for wildlife. Fire is a natural part of our ecosystems, but decades of fire suppression led to too much fuel build up and human activities increase the risk of a spark. Couple these factors with longer, hotter fire seasons due to climate change and its a recipe for disaster. It’s hard to fault our ancestors, who only sought to save human life and property by suppressing every fire in the forest. It’s easy to berate them for their lack of understanding of core ecosystem processes, but that’s like faulting Newton for not understanding black holes. Science happens at its own pace and we create management plans with the best information we have.

But that was then.

Fires have become increasingly more intense and more frequent due to our actions on the landscape and climate change. We build homes in the beautiful woodlands only to watch them burn as embers jump from shingle to shingle. Gone are the days where we suppress every fire. But also, gone are the days where we can afford to let every fire burn. Many fire ecologists tout the benefits of letting fires burn but as the risk to human health increases, the cost of fires on our own species isn’t something we scientists can ignore in the ivory tower.

The week before Thanksgiving 2018, smoke coated the Central Valley of California and seeped into the Bay Area. The hell of a fire season wasn’t over. Schools were canceled, and a group of UC Davis students gathered on the quad to throw rocks at the smoke in a purely symbolic effort to get our town back. It was rough where we were. But just up the road, a mere 100 miles away, the town of Paradise was burning.

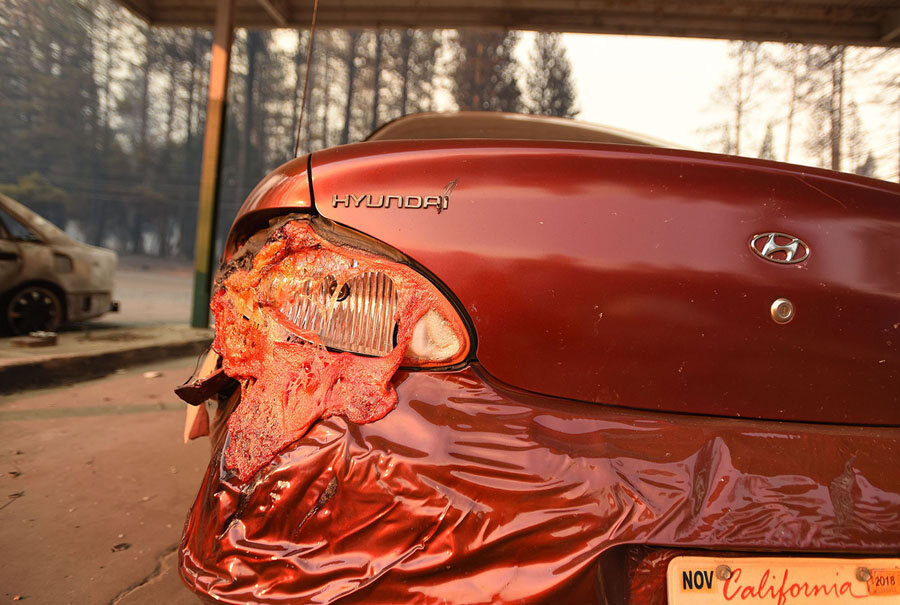

The above photos were taken during the Camp Fire that ravaged Paradise, California. Image credits: Josh Edelman/ AFP/ Getty

I have never personally experienced a wildfire. I have been the host to evacuees as a camp counselor in Colorado during 2012’s destructive fire season. I have explored the ashes searching for surviving seeds and signs of life after the Mendocino Complex forest fire. But I have never experienced firsthand the devastation that a wildfire brings.

In Paradise, homes were destroyed, family members lost, whole livelihoods went up in smoke. The residents lost everything: homes, photo albums, decades of family heirlooms, any evidence of the life they once lived--incinerated. Today, many of Paradise’s residents are still living in Chico, and many may never return.

When these catastrophic wildfires strike our communities, it is hard to make the case that fire is good. Fire is devastating. Fire is life-threatening. And are these types of fires natural?

This figure shows the annual wildlife-burned area from 1983 to 2015. Without a doubt, the area of land burned by forest fires every year is increasing. Credit: EPA

The paleoclimate record indicates that before 1800, 1.8 million hectares of California burned annually, but the fires of this same magnitude were described as “extreme” in the 20th and 21st centuries. The difference being this:we are now in a state of nearly 40 million people, with 30% of homes within 1.5 miles of dense vegetation (California Department of Insurance, 2018). Despite how “natural” they once were, fires are now a threat to human life, and the U.S. Forest Service is forced to prioritize protecting lives and property over environmental well-being (U.S. Forest Service).

Credit: Lawrence Sawyer/Getty

The relationship between fire and ecology is complex. Some ecosystems evolved with fire and need it to thrive. Others hardly ever burn, and when they do it can fundamentally alter the plant community by increasing exotic plant invasion and decreasing the ecosystem function. An unfortunate series of droughts, increasing population, tree death, low budgets, climate change, and mismanagement of energy companies (looking at you, PG&E) has changed the fire regime and we can no longer justify these massive fire storms as “the historic normal.”

It is my job to think about how fires affect ecosystems and the politician’s job to think about how they affect people. But the two go hand in hand. We haven’t seen the last of these megafires, and if we are going to prepare for our new normal, we need to understand both the ecosystem effects and how they will influence our growing population.

As of November 3, California has experienced over 6,000 wildfires in 2019 with utility shut-offs and evacuations impacting people across the state. It’s probably valid to say we’ve brought this on ourselves via climate change inaction, poorly managed utilities, and decades of fire suppression, but arguing about who to blame won’t get us anywhere.

We need policies. We need research on the effects of extreme fires on both ecosystems and people. This is the new normal, and we need to find ways to deal with it.

-Brianne